As the Bashar-Al-Assad led Syrian government takes control of Aleppo once again, the usual suspects have begun a reinvigorated smear campaign against the infamous dictator. But Russia’s involvement on the ground has ensured the world also gets a narrative different from the Western one this time around.

A clearer picture of the anti-Assad rebels supported by the Americans is finally emerging: radical, brutal, living the good life and letting the captives die of hunger.

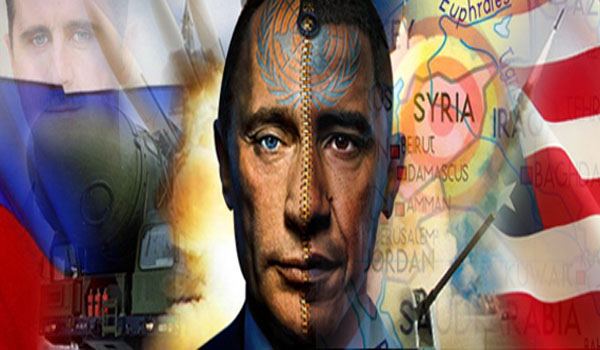

As the Assad camp continues to make fresh inroads and reclaim lost territory, Russian president Vladmir Putin’s blockbuster 2016 is showing no sign of slowing down. Contrary to what was believed initially, the happenings in Syria are neither an extension of the Arab Spring, nor a Sunni-Shia battleground. It is widely accepted that the Syrian war is a cold-war style proxy war between the Americans and the Russians. That it has gone very out of hand on the American end is another matter.

Many were surprised when Russia decided to join the war last year. Several reasons were attributed to this move: diverting attention from Ukraine, reinforcing the fact that they continue to be an important world power, and bailing out a friendly regime. But there are several indications now that the situation isn’t so straightforward. The confident locking of horns with the Americans over a controversial dictatorial regime, the way they continue to fight hard on the ground despite having arrived at a never-ending impasse over conference tables, suggest that there is much more at stake than what meets the eye.

At the centre of this conflict is Bashar-Al-Assad. That the Russians want him to stay and the Americans want him to go is common knowledge.

What is surprising is the extent to which both sides have pursued their agendas. Would the Americans arm random militants to take on a regime simply because they refuse to buy arms from them, or because a small group of Syrians decide to go too far with the Arab Spring hangover? Would the Russians, on the backfoot geopolitically one year ago, jump full-fledged into a conflict because it involved one of their allies? And that too when the ally seemed to be managing fine alone?

The Syrian war must be perceived in the larger context. In between the breaking apart of the Soviet Union and the advent of Vladmir Putin, the Americans believed that they had successfully cut Russia to size. But ever since he took office, Putin has been on a quest to reclaim the empire’s past glory. This naturally makes him America’s primary enemy, and much of recent American foreign policy has cutting Putin to size as its basis.

Back in Russia, there is widespread support for Putin and his worldview. The Americans believe that the only way they can subdue Putin’s bold agenda is by hitting Russia where it hurts- by going after its economy. Several sanctions of various kinds have been imposed through the years. Each one has been a spectacular failure. This is because of Europe’s complete dependence on Russian energy, something no amount of sanctions can affect. The only possible substitute for Europe’s energy requirements is Saudi Arabia. No other country has both the capacity of supplying at such a large scale and the resources to set up supply infrastructure. After gaining a foothold in Iraq and having an old ally in Turkey on the other side, all the Americans had to do to cut Russia out, was to remove Assad from Syria and get the pipelines up and running.

Considering the nonsensical grounds Bush used to invade Iraq, it is entirely possible that this was a long term American strategy to isolate Moscow. The bipartisan support for the Iraq war indicates in retrospect that America’s core foreign policy interests are independent of the administration’s political allegiance. If that is the case, Obama was simply attempting to complete the second leg of a quest which began during the Bush era. But where Bush succeeded, Obama failed.

Obama rode to power in the backdrop of the 2008 financial crisis. Among the planks on which he fought the elections was the withdrawal of troops from the Middle East. More than upholding a campaign promise, it made a lot of sense financially for the Americans to withdraw from the Middle East. It saved them several billion dollars, which were better spent reviving the economy. Unable to afford a full-fledged war and led by a president who cared more about his legacy than anything else, the Americans had several constraints this time around to achieve the same foreign policy objective.

At the fag-end of the Arab Spring, the Western media began peddling the narrative that the spate of uprisings had spilled over into Syria. Syria is a dictatorship, and the existence of certain disgruntled elements hardly comes as a surprise. However, the high level of discontentment against the Assad regime as portrayed in the Western media is highly questionable. Very soon, the Americans asked Assad to step aside. Upon the rejection of their request, they began supporting and arming anti-Assad groups in the country. Unable to afford boots on the ground, they used the media narrative as a pretext to arm these groups and destabilize the government.

The anti-Assad groups were essentially Sunni terrorist organisations. Along with the Americans, the Saudi Arabians began funding these groups as well. Several Saudi businessmen poured millions of dollars into these organisations, with the hope of replacing the Assad administration with a Sunni one. These groups became known as ‘the rebels’ in the Western narrative. They fought the Syrian army, but not in a coordinated way. In fact, they even refused to coordinate with their sponsors once they were armed and ready for battle. The Americans continued to pour money, but were gradually losing the plot. Each of these groups had their own agenda, and wanted to carve out their own little fiefdom.

The best example of one such group is the Islamic State. Essentially a rebel group that grew in size and stature, it established a caliphate in the region with the help of Saddam Hussein’s former soldiers. The Americans probably realised by then that things had gotten out of hand, but were clueless as to how to go about it from thereon. Only when Jihadi John’s videos of beheading journalists and a host of propaganda material surfaced on the internet, that the world realise what turn the entire situation had taken.

The Americans were forced to accept that some of the rebels were indeed more dangerous than Assad, and that dealing with them was the priority. At this point, Russia got into the war. The timing was perfect. The Americans had no clue as to whom they were funding and arming. And courtesy the Islamic State, Russia now had the license to go after the so-called rebels.

One year on, the Syrian government is gradually reclaiming lost territory. Russian help is enhancing their efforts. The rebels remain more divided than ever, and America’s constraints regarding boots on the ground remain the same. For the Russians, Assad needs to stick to power for the sake of their economy. For Assad, it is a battle he is currently winning. But as it stretches into eternity, whether he holds his nerve or not remains to be seen.