Scientists, rights campaigners, and delegates from almost 200 countries convened in Canada for the COP 15 biodiversity conference to address one of the world’s most important environmental issues: biodiversity loss and what can be done to reverse it. Throughout the convention, African countries have shown extraordinary tenacity in pressing industrialised countries and the United Nations to institutionalise the African continent’s demands.

For years, experts have sounded the alarm over how climate change and other factors are leading to an “unprecedented” decline in animals, plants, and other species, and threatening various ecosystems.

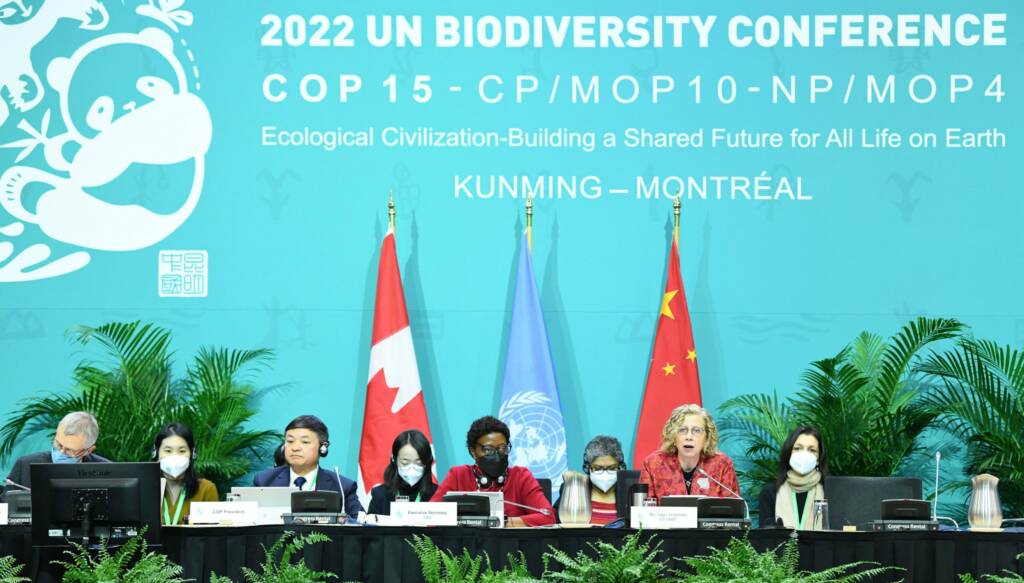

Against that backdrop, the United Nations’ biodiversity conference, known as COP15, began its sessions in Montreal with the aim of setting out a plan to tackle global biodiversity loss over the next decade and beyond.

The December 7-19 COP 15 Biodiversity Conference brought together representatives from the 196 countries that have ratified the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (PDF), which dates back to 1992. Scientists, non-governmental groups, and other experts were also present.

The delegations in the COP 15 Biodiversity Conference approved a global deal to protect nature and direct billions of dollars towards conservation but objections from key African nations, home to large tracts of tropical rainforest, held up its final passage.

African countries bemoaned the outcome of a recent summit on endangered species preservation, claiming that the treaty was shaped to favour certain industrialised countries. African countries such as Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Angola voiced dismay at how the summit concluded. They accused Huang Runqiu, the Chinese COP15 president, of pushing the agreement through despite African countries’ reservations.

“You have twisted the procedure that you yourself announced. You had announced that the documents would be individually adopted. What you did, just a minute ago, was basically a force of hand,” a Cameroon negotiator said in protest in the negotiation hall.

The DR Congo’s environment minister, Eve Bazaiba, said that her country didn’t support the Global Biodiversity Framework because of the state of the financial target. The country had wanted developed nations to pay into a new fund akin to the one that was agreed upon at the UN climate conference (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt in November.

You see, since 1995, COP summits have served as the principal international platform for climate negotiations. While the summit is supposed to represent the concerns and objectives of all the participating nations, this remains only a distant dream. Frankly speaking, there is no doubt that the contemporary environmental movement enforces the perceptions of primarily affluent, at-ease Americans and Europeans on predominantly destitute, poor Africans, Asians, and Latin Americans. It infringes on these people’s most fundamental human rights by denying them access to the economy, the ability to live better lives, and the right to rid their nations of diseases that were wiped out in Europe and the United States way before.

The world’s wealthiest nations are disproportionately responsible for global warming to date. However, the majority of the costs and effects of the climate catastrophe are borne by vulnerable populations, women, and indigenous people in the world’s poorest nations, despite the fact that they have a negligible portion of the blame. Rich nations, on the other hand, who have historically benefited from environmental plunder, largely remain unaffected.

Rather than providing cash and financial support to the developing countries in their efforts to combat climate change, industrialised countries, due to their dominance in international organisations like the United Nations, continue to place onerous demands on the developing nations.

The recent display of strength by African nations was thus historic. Africa has made it crystal clear that fairness and “common but differentiated responsibilities” must be the cornerstones of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations. They would no longer accept the imposition of climate mitigation programmes created by Western nations for hedonistic advantages. The meeting provided an opportunity for African nations to make a crucial point: Ecological imperialism will be opposed with all of their power.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6LcIDEsuRk