Protests in Peru since early December have led to the deaths of at least 48 people as demonstrators have clashed with security forces in the Andean country’s worst outbreak of violence in over 20 years.

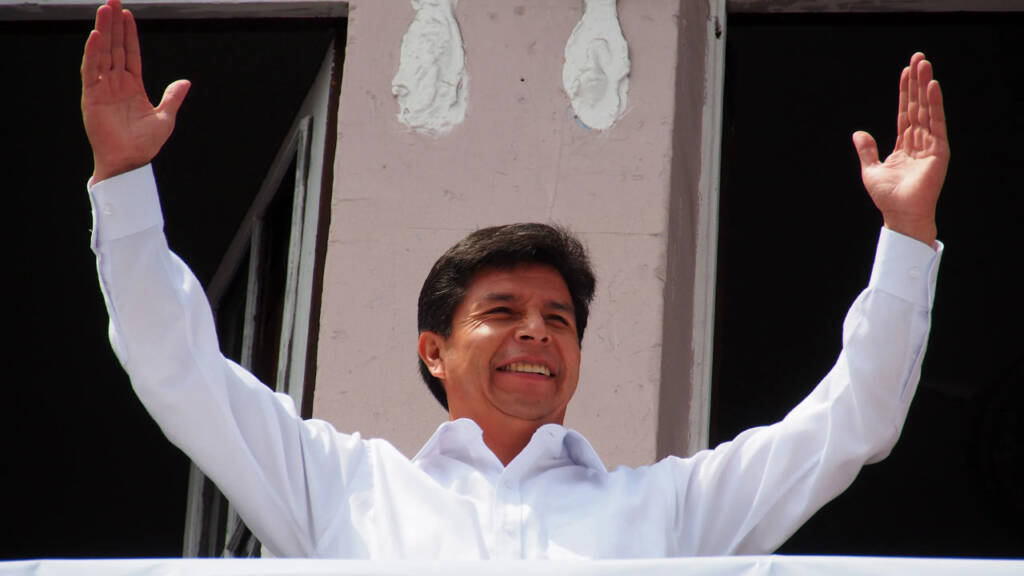

The protests began in Peru after Congress removed President Pedro Castillo on December 7. Castillo was arrested and is being held in pre-trial detention, facing rebellion charges after he tried to illegally dissolve the legislature to avoid a planned impeachment vote.

His removal fueled anti-elite sentiment, particularly in poor rural Andean regions in Peru’s south, which had catapulted Castillo, a Marxist school teacher and political newcomer, to the presidency in 2021.

The deaths in the protests of Peru have fueled even more rage, with protesters brandishing posters labelling President Boluarte a murderer and accusing authorities of “massacres.”

Protesters have shut down roads, taken over airports, and set some buildings on fire in order to demand West-backed Boluarte’s resignation, the shutdown of Congress, a new constitution, and Castillo’s release. There have also been protests to put an end to the disturbance.

To be clear, having rapid new elections is critical to ending the conflict. Congress initially supported delaying the scheduled 2026 election to April 2024, but there is increasing pressure to hold the election later this year.

However, because Congress is deeply divided, politicians are trying to reach an agreement on new laws that would allow the country to hold elections in 2023.

Fragmentation has been a serious issue for the country. Peru has produced steady economic development and remarkable reductions in poverty and inequality over the last three decades. Despite occasional crises, its political system has remained firmly democratic since 2001, with regular free and fair elections; notable, presidents are constitutionally barred from running for reelection immediately (that is, a former president can only seek reelection once he or she has been out of office for a full five-year term). Its party system, on the other hand, has become extremely fragmented, with multiple established and newly formed parties competing in each presidential and legislative election, resulting in an increasingly dysfunctional relationship between the unicameral Congress of the Republic and the executive branch.

Peru’s partisan system’s hyper-fragmentation and fast turnover have made it increasingly impossible for the government to function. Parties may establish coalitions to block legislation much more easily in such a fragmented system than they can form coalitions to legislate.

Parties in Peru have mostly become vehicles for individual success; they can elect presidents but are unable to garner support for their goals in Congress once elected. The plethora of parties has enhanced the temptation for vote buying; Peru’s Congress is notably riddled with people who switch party loyalties based on who offers the best price. Voters’ trust in politicians is harmed further by an election system that, in practice, favours corruption in the form of “money laundering” to fund campaigns.

Also Read: Evo Morales will not let Peru meet Bolivia’s fate

Peru’s current legislative impasse is a result of the peculiarities of the country’s existing system of “checks and balances,” yet such a system is not fixed; a constitutional convention might remedy its flaws methodically. A convention might also alter elements of the 1993 constitution that are overly friendly to natural resource extraction firms and other special interests, all while working to make Peruvian society more inclusive and egalitarian.

For decades, Peruvians have had very low expectations of the state, and the state has failed to achieve even those low expectations. It is time for Peruvians to expect more and for Peru’s many interests—social, economic, cultural, and political—to advocate for such demands to be satisfied.