In a groundbreaking marine expedition, a French-led team of scientists is preparing to set sail from the port city of Brest on June 15 in search of more than 200,000 barrels of radioactive waste dumped decades ago into the depths of the northeast Atlantic Ocean.

The mission, organized by France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), the French national ocean science agency Ifremer, and the French oceanographic fleet, aims to map and assess the state of submerged barrels that were discarded between 1946 and 1993 by multiple European countries.

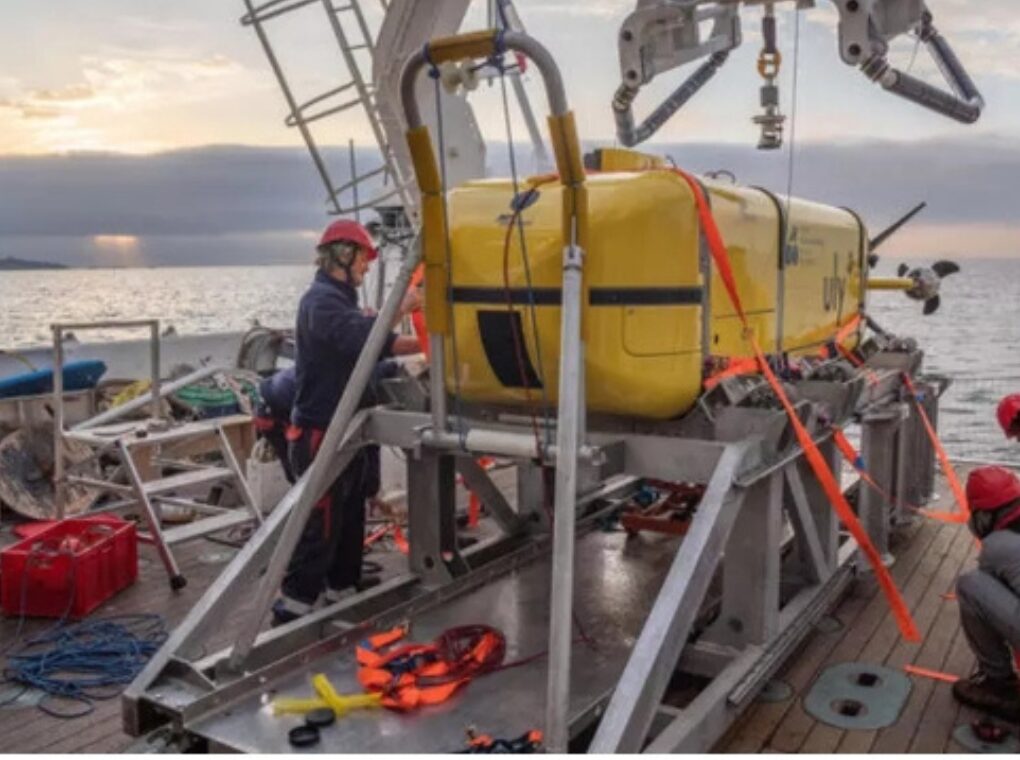

Equipped with the cutting-edge UlyX underwater robot, the team will explore depths of up to 6,000 meters in one of the most concentrated zones of nuclear marine waste in the world. The autonomous robot, measuring 4.5 meters long, will use sonar technology and high-resolution cameras to locate the barrels and evaluate their condition.

The Legacy of Nuclear Dumping

From the end of World War II until the early 1990s, 14 nations, including France and the United Kingdom, disposed of low- to medium-level radioactive waste at over 80 sites across the Arctic, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. It was widely considered a safe method of disposal at the time. However, many of the barrels have now long exceeded their estimated durability of 20–26 years.

Most of the waste was encased in asphalt or concrete before being sealed in watertight barrels. While high-level waste was not typically dumped, environmental experts warn that the long-term behavior of radionuclides in deep-sea ecosystems remains poorly understood.

A 2000 investigation by Greenpeace at one such site—the Casquets trench in the English Channel—revealed heavily corroded barrels, sparking renewed concern over the environmental impact of this hidden nuclear legacy.

A Mission of Modern Precision

Unlike previous missions in the 1980s and 1990s that relied on limited technology, this expedition is expected to produce a detailed map of the radioactive dumping zones. The UlyX robot will scan the ocean floor and photograph the barrels, allowing scientists to measure radiation levels in surrounding water, sediment, and deep-sea organisms.

“This is not a mission to pass judgment on past actions,” said co-lead scientist Javier Escartin. “We are focused on understanding the current state of the environment and how these waste materials are interacting with ocean ecosystems today.”

The research team will initially cover a fraction of the estimated 6,000 square kilometers that make up the Northeast Atlantic dumping site. Each dive by the UlyX robot will cover about 20 square kilometers, making the expedition a small but significant step in what could become a much broader investigation.

Potential Biological Risks

One major concern is the possibility of radionuclides like strontium-90, a known calcium mimic, entering marine food chains. “Strontium-90 can be absorbed by marine life in place of calcium,” said Patrick Chardon, a nuclear environmental specialist from the Clermont Auvergne Physics Laboratory. “If that happens, it could impact a wide array of species, including those humans consume.”

While some radioactive materials decay relatively quickly—cesium-134, for example, has a half-life of about two years—others, such as uranium-238, persist for billions of years. Understanding which elements remain mobile and biologically active is a key goal of the mission.

Transparency and Public Data

All findings from the mission will be made publicly available in the interest of scientific transparency. A follow-up mission is already being planned to deepen the research and expand the geographical scope of exploration.

“The data will help us understand whether these barrels continue to pose a threat and how marine ecosystems may have been affected,” Escartin added.

Though a full inventory of the waste is still far from completion, the mission represents a vital effort to confront a little-known and largely invisible environmental legacy. It may also provide crucial lessons for future nuclear waste management and long-term ocean conservation.