In a picturesque Swedish meadow outside the city of Västerås stands a timber-clad, onion-domed Russian Orthodox church. To a casual observer, it looks like a serene place of worship nestled in nature. But Swedish intelligence sees something far more troubling: a possible outpost in Russia’s hybrid war playbook.

Located just 300 meters from the strategically vital Stockholm-Västerås Airport, the Church of the Holy Mother of God of Kazan has come under intense scrutiny. Swedish security services believe the church — built by the Kremlin-aligned Moscow Patriarchate — may be serving as a platform for espionage and influence operations in the Nordic country.

A Church Built on Red Flags

The church’s construction raised concerns long before its completion in late 2023. Approved despite zoning restrictions limiting its spire height due to proximity to an airport — a detail that was somehow overlooked — the 22-meter structure now looms just beyond the perimeter of Sweden’s third-largest runway, once a Cold War-era air force base and now a hub of NATO activity.

Local journalist Mikaela Lundblad was among the first to investigate. “There were red flags from the start,” she said, pointing to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and heightened warnings from Sweden’s intelligence agency SAPO.

That suspicion has since hardened into official concern. SAPO declared in late 2023 that the Moscow Patriarchate in Sweden was being used by Russia to “gather intelligence and conduct activities threatening national security.”

A Strategic Location — And a Strategic Asset?

The church’s location isn’t just curious — it’s strategic. Västerås sits on the edge of Lake Mälaren, a critical corridor connecting Sweden’s heartland to the Baltic Sea. Key bridges, highways like the E18, and military communications infrastructure are all within striking distance.

Andreas Nyqvist, head of the VST airport control tower, says the situation makes him uneasy: “Nothing is normal about a church that close to the airport.”

Security experts like Patrik Oksanen believe this is no coincidence. “Look at the map,” he urges. “The church’s location isn’t about religion. It’s about access — and surveillance.”

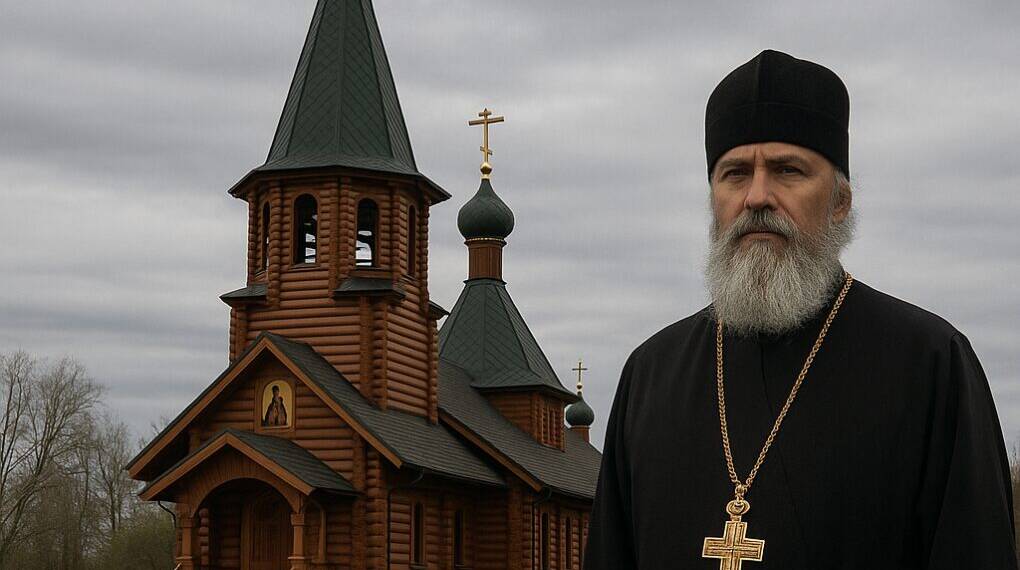

The Priest, the Medal, and the Money Trail

At the heart of the story is 68-year-old Father Pavel Makarenko, the church’s elusive leader. Once media-friendly, Makarenko has since retreated from the public eye. His past includes a conviction for accounting fraud linked to a Russian Belarusian trade firm and alleged ties to Russian intelligence.

In a particularly revealing twist, Makarenko was reportedly awarded a medal of service by Russia’s foreign intelligence agency, the SVR, during the church’s 2023 inauguration. Security experts confirm the medal appears authentic.

Also present at the inauguration were key Russian figures, including diplomats and Metropolitan Anton of Volokolamsk, a top ROC MP official. The event was sponsored in part by a Kremlin-linked foundation run by Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear agency.

Church or Trojan Horse?

The Russian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate (ROC MP) is no ordinary religious body. Long intertwined with the Kremlin, it’s been called an “instrument of soft power” — a religious front with political purpose.

Experts note the ROC MP frequently serves as a vehicle for Russian influence abroad, opening churches and NGOs in strategic locations. In Ukraine, some Russian Orthodox churches were reportedly used as safe houses and weapons caches. In Sweden, intelligence officials fear a similar agenda.

“The ROC MP is part of the Kremlin’s power apparatus,” said Vladimir Liparteliani, a researcher at Durham University. “It’s churches abroad can double as operational platforms.”

More Than One Church

The Västerås church is not alone. Other ROC MP attempts to gain influence in Sweden have followed a familiar pattern — and sparked pushback.

In 2019, Father Angel, head of Sweden’s oldest Russian Orthodox church in central Stockholm, fought off a takeover attempt from pro-Moscow forces. He recalls a sudden influx of new membership applications, likely a bid to install pro-Kremlin leadership through a vote. “They tried to stage a coup,” he said.

Elsewhere in the Stockholm suburb of Aspudden, a small wooden chapel — St. Sigfrids — was overtaken in 2020 after its tenants from the ROC MP refused to leave. Locks were changed, accounts frozen, and a hidden camera was discovered. Only after four years and legal intervention did the original caretakers regain control.

“They stole this church,” said volunteer pastor Kåre Strindberg. “They forgot the seventh commandment: Thou shalt not steal.”

A Broader Pattern

Sweden is not alone in raising the alarm. In 2023, Bulgaria expelled the national head of the Moscow Patriarchate for suspected espionage. In the U.S., the FBI issued a warning about Orthodox churches potentially being used as cover for Russian agents.

In Sweden, authorities have now cut public funding to all Moscow Patriarchate-linked congregations. The city of Västerås is considering expropriating the land on which the church stands, citing national security risks.

Yet the ROC MP’s map of planned European “projects” continues to expand. At least a dozen are in development, raising urgent questions about how open societies should respond to what some call “religious occupation.”

Looking Ahead

For now, the Church of the Holy Mother of God of Kazan stands behind steel fences and tinted windows, its priest unreachable and its purpose increasingly unclear. The birds still chirp in the meadow, but the hum of nearby NATO drills and the whir of surveillance cameras remind locals that not everything is as peaceful as it seems.

As Sweden navigates its new role within NATO and faces escalating tensions with Moscow, one church near a quiet forest path may serve as a symbol — and a warning — of the silent battles being fought in plain sight.