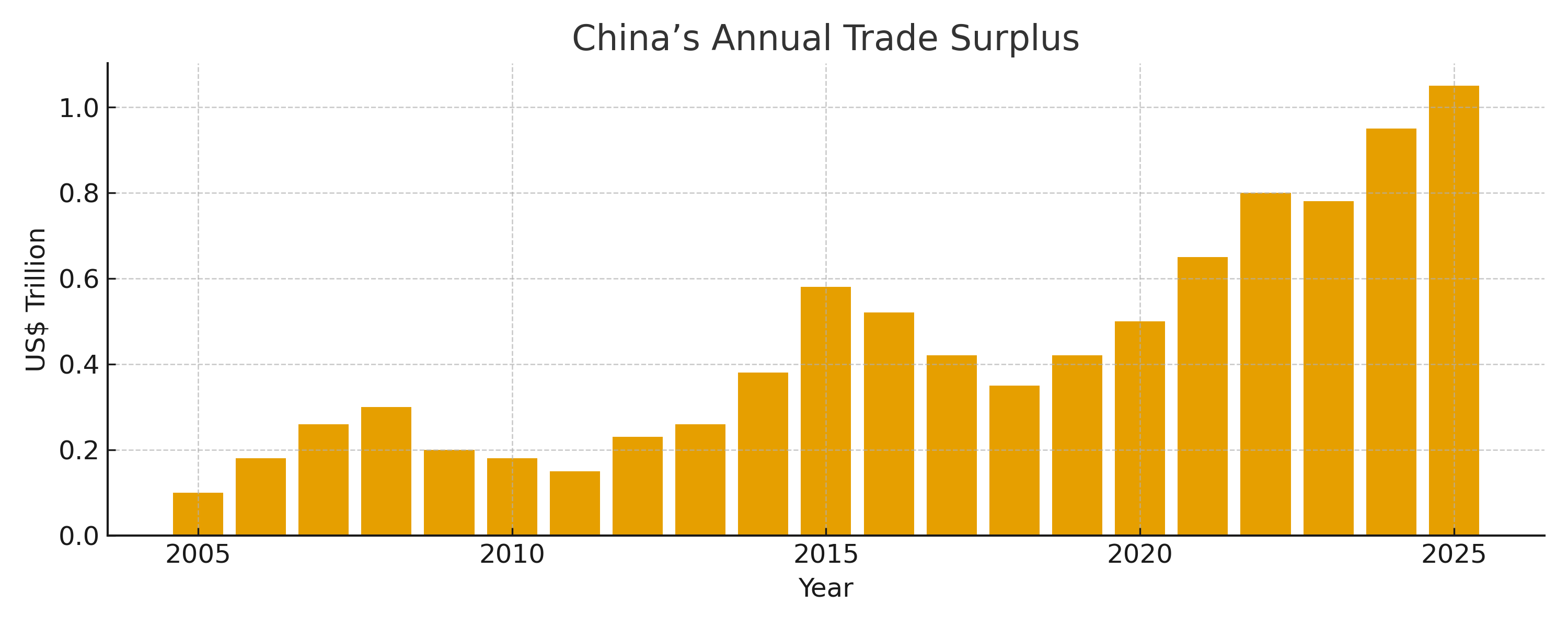

China has once again stunned the world by breaking a historic trade record. In just the first 11 months of this year, China’s trade surplus in goods and services has reached $1.08 trillion, a level no country has ever achieved so quickly. This milestone underlines not only China’s export strength but also its growing influence over global trade, industry, and geopolitics.

A Record-Breaking Export Surge

China first drew global attention last year when its trade surplus neared $1 trillion over a full year. This year, it has crossed that mark well before December despite the tariff war. According to China’s customs authority, the surplus rose sharply despite tariffs imposed by US President Donald Trump.

Even though Chinese exports to the US fell by nearly 20% due to tariffs, China reduced its imports from the US—such as soybeans and other goods—by a similar margin. As a result, China continues to sell three times more to the US than it buys.

In November alone, China posted a surplus of $111.68 billion, its third-largest monthly figure on record. Overall, the surplus for January to November is 21.7% higher than the same period last year.

Flood of Chinese Goods Across the World

China’s export push is no longer limited to the US. Chinese products—ranging from cars and solar panels to consumer electronics—are flooding Europe, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Major manufacturing powers such as Germany, Japan, and South Korea are losing market share to cheaper Chinese goods. At the same time, factories in developing countries like Indonesia and South Africa are being forced to reduce output or shut down because they cannot compete with China’s low prices.

To get around US tariffs, many Chinese companies have shifted final assembly to countries like Vietnam, Mexico, and parts of Africa, from where finished goods are exported to the US. This strategy allows China to maintain its export dominance while technically avoiding direct tariff penalties.

Europe Feels the Pressure

China’s surplus with the European Union has expanded sharply this year. China now exports more than twice as much to Europe as it imports from the region.

One key reason is the weak Chinese currency (renminbi). Over recent years, the renminbi has remained low against major currencies, especially the euro. At the same time, prices inside China have fallen, while costs in Europe and the US have risen, making Chinese goods even more attractive.

According to the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, the renminbi may be undervalued by as much as 30% against the euro. This makes fair competition extremely difficult for European manufacturers, even if Europe reforms its own markets and reduces energy costs.

Why This Matters for Global Politics

China’s trade surplus in manufactured goods now makes up more than a tenth of its entire economy, a level higher than even the US enjoyed after World War II.

This export power funds China’s rapid technological growth and strengthens Beijing’s geopolitical position. It also gives China financial capacity to support friendly authoritarian regimes such as Russia, North Korea, and Iran, adding a strategic dimension to what appears to be an economic story.

Recognizing the risks, senior officials from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are visiting China this week to review its currency and financial policies.

Debate Inside China

A growing number of Chinese economists are urging Beijing to allow the renminbi to strengthen. A stronger currency would make imported goods—fuel, foreign food, cosmetics, and consumer products—cheaper for Chinese households, helping revive domestic consumption.

Boosting consumer spending is one of China’s top policy goals. However, a stronger renminbi would also hurt exporters, reduce factory profits, and potentially slow job creation—making the decision politically sensitive.

Some economists argue that China may eventually need to accept a smaller trade surplus, or even a trade deficit, to improve living standards at home.

As China’s export engine powers ahead, its economic choices are no longer just domestic decisions—they are shaping global markets, political alliances, and the future balance of power in the international system.