The federal government has been quietly strengthening commercial and military relations with the Indo-Pacific allies, but foreign policy experts believe Ottawa’s reluctance to give a more comprehensive strategy in the region stems from concerns about upsetting China. According to persons familiar with the matter, officials at Global Affairs Canada have been working on an Indo-Pacific strategy since about April 2019, but despite growing relationships in the region, Ottawa has been quiet in public pronouncements about the region.

Ottawa began formal free trade talks with Indonesia earlier this year and has been in separate multilateral talks with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a ten-country grouping, since 2017. Canada has also boosted its involvement in regional joint military exercises, including two anti-submarine warfare drills, and has sailed naval ships through the Taiwan Strait on occasion, in what some see as a threat to China’s claims to sovereignty over the self-governed territory.

On Thursday, Global Affairs Canada refused to say when a strategy would be made public. Observers ascribe the silence to the Liberal government’s concerns about escalating an already tense relationship with China.

Margaret McCuaig-Johnston, a former member of the Canada-China Joint Committee on Science and Technology and a senior official in the Department of Finance from 1994 to 2004, speculated, “They may be trying to figure out how to present it in such a way that it doesn’t look like it’s a pushback against China, which might make China angry at a point where we don’t want to poke the dragon.”

For years, trade and foreign policy experts have argued that Canada should develop a strong strategy in the Indo-Pacific region, claiming that doing so would diversify Canadian exports and preserve vital supply chains.

Semiconductor supplies, for example, are mainly concentrated in the Indo-Pacific area, whereas agricultural exports such as canola in Canada are mainly reliant on China. Many Canadian companies operating in China have faced intellectual property issues, according to Johnston, prompting her to urge for a policy to assist business owners in diversifying their operations to other nations. “The more points of engagement you have with China, the more places they have to turn the screws,” Johnston said.

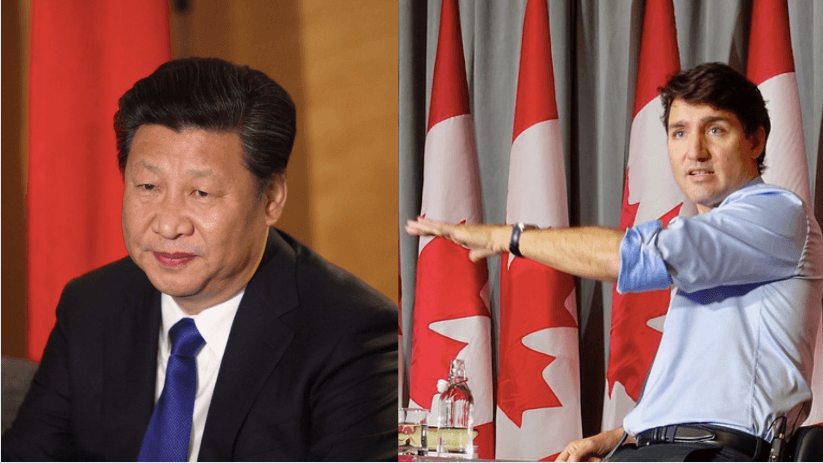

Since Canadian authorities detained Meng Wanzhou, the chief financial officer of Chinese technology giant Huawei, on a US extradition request, relations between the two nations have deteriorated. Since then, the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has attempted to contain further squabbles, particularly after China jailed two Canadian citizens — Michal Kovrig and Michael Spavor — in retribution for Meng’s detention.

According to a report from Japan’s foreign ministry, Foreign Affairs Minister Marc Garneau met with his Japanese counterpart Toshimitsu Motegi on May 3 and the two “shared their serious concerns” about human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, as well as China’s “persistent attempts” to claim sovereignty over disputed territories. In contrast, Garneau’s office’s summary of the same meeting was significantly more modest, referring merely to “relations with China” in general. “They’ve been very publicly quiet on this,” said Jonathan Berkshire Miller, director of the Indo-Pacific program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Garneau’s meeting came after Trudeau and former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe held high-level talks in 2019, during which the two highlighted the importance of maintaining a “free and open Indo-Pacific area.” In 2018, Canada ratified the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multilateral trade agreement. Miller understands Ottawa’s cautious approach on the subject, arguing that a wide Indo-Pacific strategy may be misinterpreted as exclusively anti-China. However, such a policy would take into account Canada’s broader interests in one of the world’s fastest-growing economic regions.

“The development of a strategy shouldn’t be seen as like a punitive measure because we’re in a downturn with China,” he said. Miller termed the Indo-Pacific “probably the world’s centre of geoeconomic and geostrategic gravity” in a lengthy study released in March, and urged Canada to “become an active player” in the region to help secure a rules-based geopolitical order.

Meanwhile, Canada is being urged to expand its military presence in the region, notably through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “the Quad,” an informal military partnership involving the United States, Japan, Australia, and India. China’s fast construction of military sites and strategic outposts in the South China Sea and elsewhere has prompted the formation of the group, which is largely seen as a response to its economic and military expansionism.

“Our absence has been remarked upon,” Trottier said. “They certainly are engaged on the economic front, and they have been welcomed on some of these steps on security and political engagement,” he said. “But it remains to be seen as to how serious and long-lasting those steps are.”

In January, Canada took part in the Quad on Sea Dragon, an anti-submarine military exercise held near the US island of Guam for the first time. Months previously, the Canadian naval ship HMCS Winnipeg took part in Keen Sword, an 11-day military exercise led by the US and Japanese forces to test combat preparedness and interoperability.

Meanwhile, Canadian ships have assisted in the enforcement of UN sanctions against North Korea. Even yet, according to James Trottier, a former Indo-Pacific diplomat and current fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, Canada’s commitment to the region has been ambiguous for decades.

Several observers argue that while Canadian politicians frequently talk about strengthening relationships in the Indo-Pacific, they rarely back up their words with concrete financing. Canada has occasionally declined to attend key regional summits or other engagements or has sent lower-level officials to gatherings attended by foreign ministers.