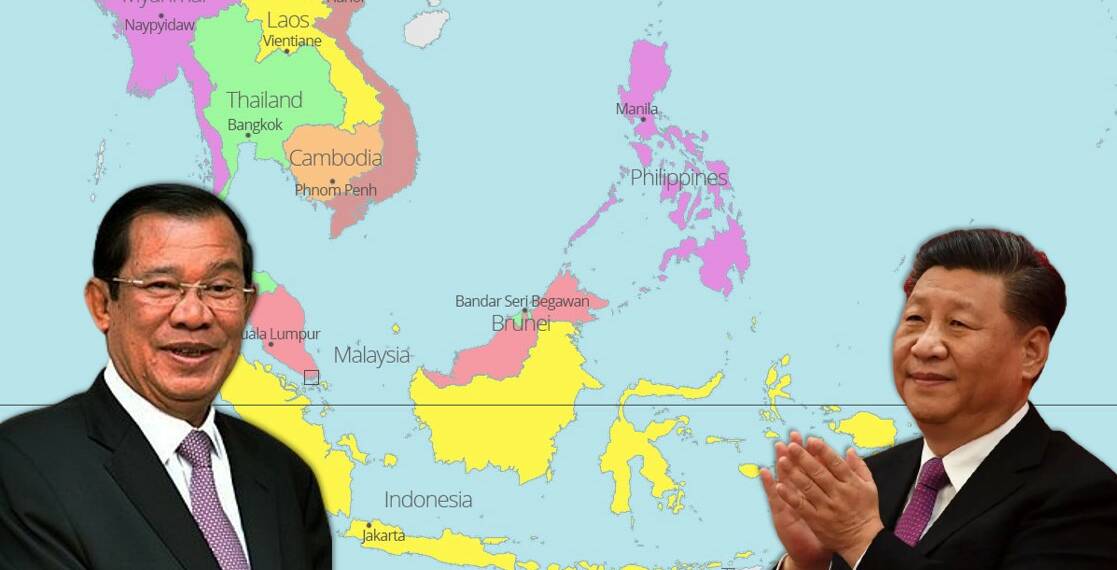

We, at TFIGlobal, had predicted that as soon as Cambodia becomes the chair of ASEAN it will start furthering the Chinese agenda in the region. And as predicted, Cambodia started following Beijing’s orders vis a vis Myanmar. According to reports, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, ASEAN’s new chair, is eager to visit post-coup Myanmar without restrictions, reversing his stance toward the Burmese junta, which even the consensus-driven regional bloc had avoided engaging with. Hun Sen, who is largely perceived as heading a pro-China authoritarian administration, is also going to invite Myanmar’s military-appointed foreign minister to Cambodia next week, according to the state-run Agence Kampuchea Presse (AKP).

What more can a military dictatorship need, other than the chair of ASEAN taking actions which can legitimise its control of a country which is engulfed in civil war as the people are not accepting this abject takeover of their democratic rights which they gained after a long struggle. In addition to this, on Monday, a special court in Myanmar’s capital sentenced the country’s deposed leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, to four years in prison for inciting and violating coronavirus prohibitions, according to a legal official. Taking both these pieces of information into consideration, we can say that the situation is fast-moving out of the hands of ASEAN.

Myanmar plus Laos and Cambodia – the drivers of China’s hegemony in the region:

We have been saying that if this trend continues, it won’t be long before China becomes the only influential player in Myanmar’s affairs. Thanks to sanctions from the west, Myanmar is close to getting ostracized on the world stage. Countries like India and Japan, however, have tried to engage the military leadership, but China’s influence remains unparalleled. And now as the developments have given a straightforward signal for the same prognosis, the bifurcation can be a reality if the ASEAN nations do not act.

Apart from Myanmar, China’s influence in Laos and Cambodia has also reached staggering levels. Laos’ external debt was approximately $9.9 billion in December 2019 just before the Covid-19 outbreak, compared to $18.9 billion in GDP for the same period. Out of this external debt of $9.9 billion, almost $5.9 billion is the amount that Laos has incurred as a loan to build the Vientiane-Boten railway project that will link its capital to China’s Kunming as part of the BRI project.

Read more: We foretold that China would split ASEAN into two groups. It has almost succeeded

And Cambodia is no different. Cambodia has a foreign debt of $9 billion, with China accounting for more than 40% of it. Cambodia’s outstanding external debt surpassed $9.18 billion in the first half of 2021 and is likely to surpass $10 billion by the end of the year, up from $8.8 billion at the end of 2020.

Cambodia’s actions and the solidification of conflict of interests in ASEAN:

“On Dec. 6-7, 2021, Cambodia will invite the foreign minister of Myanmar to visit the Kingdom … and I am also ready to travel to Myanmar without any preconditions as Prime Minister of Cambodia,” the news agency quoted Hun Sen at an inauguration ceremony for public works projects in Sihanoukville. “I am thinking whether we should keep ASEAN nine or ASEAN 10, because, in the recent ASEAN Summit, we have only 9, this is a problem,” he said.

“Are we willing to destroy our own house to please others? ASEAN must not be compared to the United Nations. …The most important point of ASEAN is the consensus, and then it should be 10, not 9.” He argues that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) should not be reduced to a nine-member bloc “to appease external partners” by removing Myanmar from regional summits. While the statement could have some weightage, but the humanitarian crisis in Myanmar and the kind of actions that Aung San Suu Kyi is facing outweigh them.

China blesses Myanmar’s Army via Cambodia, then came actions against Aung San Suu Kyi:

The 76-year-old Nobel Prize winner was sentenced for the first time in a series of prosecutions since the army seized power on Feb. 1, stopping her National League for Democracy party from starting a second five-year term in office. The incitement accusation stemmed from words she made on her party’s Facebook page after she and other party leaders had already been jailed by the military, while the coronavirus charge was from a campaign appearance before November’s elections, which her party won convincingly.

The court’s decision was delivered by a legal professional who requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation from the authorities. The trials of Aung San Suu Kyi remain closed to the public and the media, and her lawyers, who had been the only source of information on the proceedings, were served with gag orders in October prohibiting them from disclosing any information. Suu Kyi’s cases are largely viewed as fabricated in order to discredit her and prevent her from participating in the next election. Anyone sentenced to prison after being convicted of a felony is barred from holding high office or becoming a legislator under the constitution.

The Burmese general who led the coup that deposed an elected government on February 1 was barred from attending because he broke an ASEAN agreement that stipulated that the bloc’s special envoy be permitted to visit Myanmar and speak with all parties involved. But since the Feb. 1 coup, the junta’s security forces have killed around 1,300 civilians and arrested close to 8,000, according to reports.

Hun Sen had harsh words for the Burmese regime when he received the ASEAN chairman’s ceremonial gavel from Brunei in October. He claimed that while ASEAN had not kicked Myanmar out of its meeting, the junta had “abandoned its right” to be there. Hun Sen now appears to believe that Myanmar has every right to be a member of ASEAN and to participate in all of its meetings and sub-meetings. Myanmar, he argues, is essentially a “broken pillar.” It is obvious that all this is happening at the behest of China, and the change in the overt stand of the ASEAN chair is as we at TFIGlobal had predicted. The Chinese Communist Party intends to bifurcate the regional grouping into two so that it can have absolute control over the resource-rich Mekong region.