In a bold move to solidify its dominance in the global electric vehicle (EV) industry, China has imposed new export restrictions on key technologies used in EV battery production and lithium processing — a decision with far-reaching consequences for global automakers and the ongoing tech rivalry with the West.

The country’s Ministry of Commerce announced this week that several advanced technologies, including those involved in battery cathode production and lithium refinement, have been added to China’s export control list. This means any overseas transfer — whether through trade, investment, or technological cooperation — will now require special government-issued licenses.

The move echoes China’s previous restrictions on rare earth magnets, a critical component used not only in EVs but also in consumer electronics and military applications. Together, the actions signal a broader strategy to wield control over essential green tech supply chains as geopolitical tensions with the United States and Europe intensify.

Why It Matters?

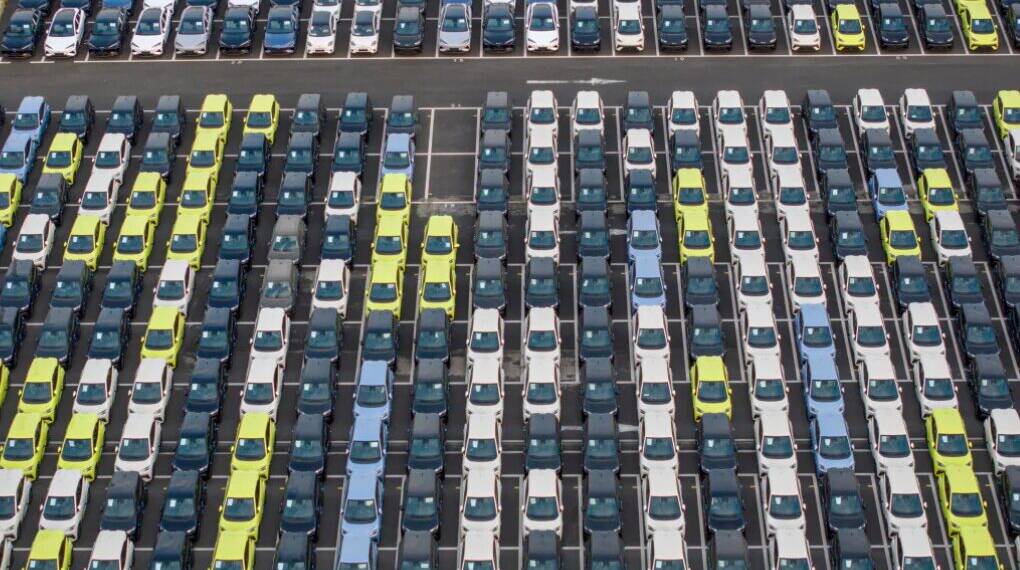

China currently accounts for 67% of the global EV battery market, according to SNE Research, and controls an overwhelming 94% of lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery production capacity. These batteries have become the go-to choice for affordable EVs, offering safety and lower cost — albeit with slightly lower energy density than nickel-based batteries.

The new restrictions specifically target upstream processes, including cathode production for LFP batteries and the extraction and refinement of lithium — two areas where China holds a commanding lead. These processes form the backbone of the EV battery supply chain, and limiting their export could complicate efforts by foreign automakers to localize battery production outside China.

A Strategic Chokepoint

“China’s move deepens the emerging geopolitical tech decoupling — shifting it beyond rare earth materials into the realm of intellectual property and process technology,” said Liz Lee, associate director at Counterpoint Research.

The restrictions come at a time when Chinese battery giants like CATL, BYD, and Gotion are rapidly expanding overseas. CATL, the world’s largest EV battery maker and a key supplier to Tesla, has opened factories in Germany and Hungary and plans a joint venture in Spain with Stellantis. Meanwhile, BYD, which overtook Tesla in 2024 to become the world’s top EV seller, has set up manufacturing bases in Hungary, Brazil, and Thailand. Gotion, another major player, is building a battery plant in Illinois.

Despite their global footprint, these Chinese firms may face delays or restrictions when transferring key technologies abroad, especially if licensing becomes a lengthy or politicized process.

Impact on Western Automakers

While the immediate impact remains uncertain, analysts believe the restrictions will likely spur Western efforts to accelerate domestic battery production and reduce reliance on Chinese supply chains.

“Even for LFP batteries made outside of China, Chinese companies often supply the precursors,” said James Edmondson of IDTechEx. “That gives China leverage even in markets where it doesn’t directly control the final product.”

China’s technological lead is also evident in innovation. BYD’s “Super E-Platform” claims to deliver 250 miles of range on just a five-minute charge, outperforming Tesla’s current Supercharger specs. CATL’s latest battery, released in April, goes even further — offering a 320-mile range with the same rapid charging time.

Rising Trade Tensions

The export controls come as the U.S. and European Union ramp up tariffs on Chinese EVs and batteries, pressuring Chinese automakers to build factories locally. China’s counter-move — limiting tech exports — reflects a shift from pure manufacturing power to supply chain and IP control.

The Chinese Commerce Ministry framed the restrictions as necessary to “safeguard national economic security and development interests,” while still promoting international cooperation.

But analysts warn that this calculated policy shift could reshape the global EV landscape, particularly if China becomes more selective or political in issuing export licenses.

The Road Ahead

At present, most of the affected processes are upstream technologies not directly used in overseas battery cell assembly. As such, near-term disruption may be limited. However, long-term risks remain high, especially if licensing becomes tighter or more selective in response to Western trade measures.

As governments in Washington and Brussels look to secure their own EV supply chains, China’s move is a reminder that dominance in green tech isn’t just about materials—it’s about mastering and protecting the process.