US President Biden’s top aides feel the time has come to meet with Iranian officials behind closed doors in Vienna, where they have been relaying communications from hotel rooms through European intermediaries because the Iranians will not meet them directly. And, according to them, the next six weeks until Ebrahim Raisi’s inauguration offers a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reach a final agreement with Iran’s leadership on a difficult issue that has been postponed.

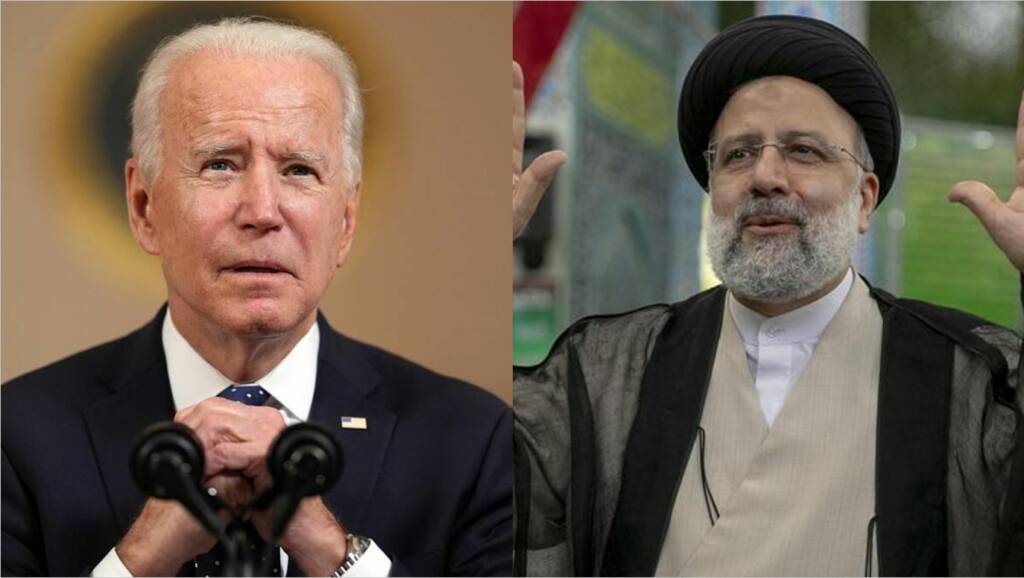

US President Joe Biden has been attempting to pacify and placate Iran since taking office. The Biden administration continues to do so in order to pursue its foreign policy agenda, which appears to be a continuation of Obama’s foreign policy. The election of Ebrahim Raisi, an ultraconservative former head of the judiciary, as Iran’s president has ignited an unexpected diplomatic drama: the establishment of a hardline regime in Iran may give the Biden administration a narrow opportunity to fix the 2015 nuclear deal with the country.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is said to want to re-establish a nuclear agreement with the West, in order to relieve the crippling sanctions that have kept Iranian oil mainly off the market. Former President Donald Trump had ripped up the nuclear deal more than three years ago on accounts that the deal did not force Iran to curb its proxies.

According to senior authorities, the resurrected deal’s particular text was hashed out just weeks ago in Vienna, the same city where the original pact was concluded six summers ago. Since then, the revived accord has sat mostly unchanged, awaiting the conclusion of an election that the ayatollah appeared to have orchestrated. Mr Raisi is one of his protégés, and many believe he is the front-runner to succeed Ayatollah Khamenei, who is now 82, as Iran’s supreme leader.

The belief in Washington and Tehran is that Ayatollah Khamenei has been orchestrating not only the election but also the nuclear talks and that he does not want to give up his best chance of freeing Iran from the sanctions that have kept its oil out of a recovering market. As a result, insiders say the ultimate decision to proceed with the deal could come in the coming weeks before Mr Raisi is sworn in and while Iran’s older — and in some ways more moderate — administration is still in power.

That means Iran’s moderates will be blamed for capitulating to the West and will face the brunt of domestic fury if sanctions relief does not help the country’s ailing economy. However, if the agreement is reached, Mr Raisi’s new conservative government would be able to claim credit for the country’s economic recovery, reinforcing his argument that the country’s recovery required a hard-line, nationalist government to stand up to Washington.

“For Iran, this is a real Nixon-goes-to-China moment,’’ said Vali Nasr, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, who is close to the negotiations. “If anyone other than the conservatives made this deal with Biden, they would be torn up,” he said of Iran’s new leadership. “The bet is that they can get away with it. No one else could.”

If Biden’s gamble pays out, and a hard-line government is a key to achieving his campaign promise of restoring a deal that was largely working before Trump cancelled it, it will be just the latest unexpected twist in an agreement that has left no one happy — not the Iranians, nor the Americans.

Trump was the most vocal opponent of the pact. He criticised Iran’s sanctions were lifted too soon, and that the agreement accomplished little to curtail Iran’s missile programme or its support for terrorist groups across the Middle East. He described the agreement as “a horrendous one-sided transaction that should have never, ever been struck” on the day he walked out of the accord.

According to sources close to the talks, there are two big roadblocks that could jeopardise Biden’s efforts to salvage the agreement. The Iranians have wanted a formal guarantee that no future American administration will be able to reverse Mr Trump’s decision to terminate the agreement. They want something long-term — “a reasonable-sounding demand that no real democracy can make,” according to one senior American official. After all, the agreement isn’t a treaty because Mr Biden, like President Barack Obama before him, couldn’t have won two-thirds of the Senate’s approval. As a result, it’s known as an “executive agreement,” which any future president, including Trump, might revoke.

The Iranians, for their part, have stated that they have no intention of modifying the terms of the agreement in a way that would further restrict production. Raisi and other candidates said during the campaign that they would not agree to any restrictions on their missile capabilities, or on their support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Iraqi Shiite militias, or Hamas, a militant group that relies heavily on Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.