Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke about economy, technology policy and other hot-button issues in his first official speech on the opening day of the Chinese parliament but he didn’t make any official statements until he was stopped by a meeting of the inner Mongolia delegation. Why? The hysteria of war has disappeared but fault lines in the Chinese society have started taking a centre stage again and Xi can soon witness an uprising against Han supremacy.

China’s policies to assimilate other ethnic regional minorities into the Han have been criticised all around the world – from using coercive physical measures in Xinjiang, to enforcing policies, to destroying the ethnic identity by systematically replacing the culture starting with language. But now Xi is becoming more apprehensive about his policies and there are no more external threats to deal with, which means that an uprising and its subsequent quashing will be heard loud and clear in China and Xi Jinping wants to avoid it at all costs.

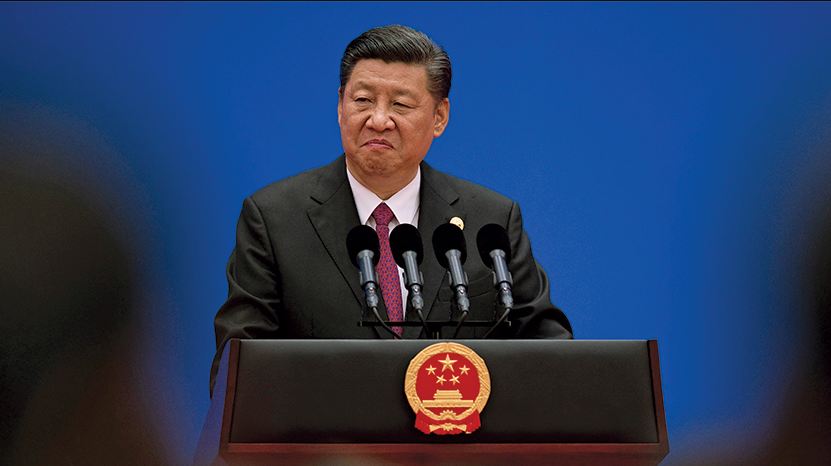

In his speech to the Inner Mongolian delegation, Xi emphasised “ethnic unity.” Protests had broken out in the region last year when authorities had further watered down the teaching of the Mongolian language. But the last year was full of external tensions for China. Border clashes with India and the inflamed trade wars with the USA had allowed Xi Jinping to deviate the attention and unite the society against external threats.

But now, the trade wars have simmered down, China and India have disengaged on the borders, and the sounds of protests and uprising will soon be heard again, not just in inner Mongolia but in Tibet and Xinjiang.

For decades, Chinese emperors have been concerned with how to govern a vast country with hundreds of distinct cultures. Language proved to be especially difficult. In 1955, the government declared a dialect spoken in and around Beijing “Putonghua,” or “popular language” and ordered it to be taught and adopted throughout the country. Other languages, which are spoken by hundreds of millions of Chinese, were reduced to the status of “dialects.”

Despite introducing a national language, the Jinping administration has also implemented policies that gave regional autonomy to China’s 55 officially recognised ethnic groups. Among other things, these included minority language protections, especially in schools, as well as economic assistance.

These policies aimed at gradually assimilating China’s diverse ethnic groups into an assimilated mainstream dominated by the Han Chinese majority (roughly 92 per cent of the population). The government has forced Han migration and investment into minority areas in order to achieve this aim for assimilation.

The tensions that have emerged as a result of this approach are most apparent in Xinjiang and Tibet, where Han migration and resource exploitation have triggered years of protests and violence. Anti-government demonstrations in both regions were increasingly unruly.

Following Xi’s ascension, a new strategy, known as “racial fusion” has emerged. It aims to assimilate minorities more vigorously than in the past, with increased protection and surveillance, as well as a strong emphasis on linguistic, cultural, and political integration.

Even though Chinese Mongolians have been a minority for decades, their assimilation has not been very successful.

In 2011, violent protests broke out over a lead mine that expanded onto nomadic grasslands. Later, the Xi Jinping administration banned a rap song recorded in response to the unrest, which included the politically pointed brag: “Yo, I am a Mongol even if I sing my rap in Chinese / No matter what you say I am a Mongol.”

In December 2020, the residents of China’s Inner Mongolia region started protesting against reforms replacing Mongolian with Mandarin as the language of instruction in schools for core classes. Critics of Beijing’s language policy in Inner Mongolia, home to an estimated 4.5 million ethnic Mongolians, said that the Chinese policies mirror efforts to assimilate local minorities into the dominant Han culture in other border areas such as Xinjiang and Tibet.

As Xi stared out over the Inner Mongolian delegation six months later, those events were undoubtedly on his mind. He urged the community to reinforce their association with “the great motherland, the Chinese nation, Chinese culture, the Communist Party of China, and socialism with Chinese characteristics,” reminding them that the Han majority and ethnic minorities are inextricably related. He reminded them that in order to do so, they would have to adopt the Chinese language and textbooks in schools.

But this time Xi does not have the comfort of external threats to bank upon to unite the nation. Mongolians, Tibetans and the Uyghur in Xinjiang have been protesting and calling for help. Last year their voices were drowned with the threat of external oppression on China. Those conditions do not exist anymore and Jinping is hysteric to calm down the waters before they turn into killer waves.